This story first appeared in a UNK News article.

KEARNEY – As a physics professor at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, Jeremy Armstrong is no stranger to asking big questions.

Thanks to a $20 million National Science Foundation-funded project, he’s tackling some of the biggest in modern science – how to harness the strange and powerful behaviors of quantum systems.

Armstrong is one of 20 faculty members participating in the Emergent Quantum Materials and Technologies (EQUATE) initiative, a multi-institution research effort focused on advancing quantum science and building the high-tech workforce of the future.

Spanning four Nebraska universities – UNK, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, University of Nebraska at Omaha and Creighton University – EQUATE brings together physicists, engineers and chemists to explore next-generation quantum materials and technologies that will revolutionize fields such as information technology, medicine, meteorology and cryptography.

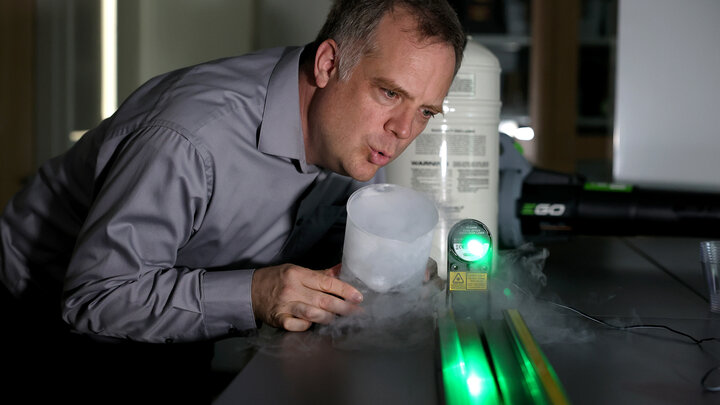

At UNK, Armstrong’s contribution centers on theoretical work involving ultra-cold quantum gases, a state of matter where atoms behave in highly coordinated and unusual ways.

“The gases I work with are dipolar gases,” he explains. “They experience long-range interactions that depend not only on distance, but on orientation, so their behavior changes depending on direction.”

Inserting impurities into these systems reveals even more intriguing dynamics, giving researchers insight into quantum behavior that could one day inform new technologies in computing, communication and sensing.

Armstrong says the EQUATE program is not only pushing science forward but also creating valuable research opportunities for students.

“I enjoy working with students outside the classroom because it’s more collaborative and you can really nurture their interests, which is very rewarding,” he said.

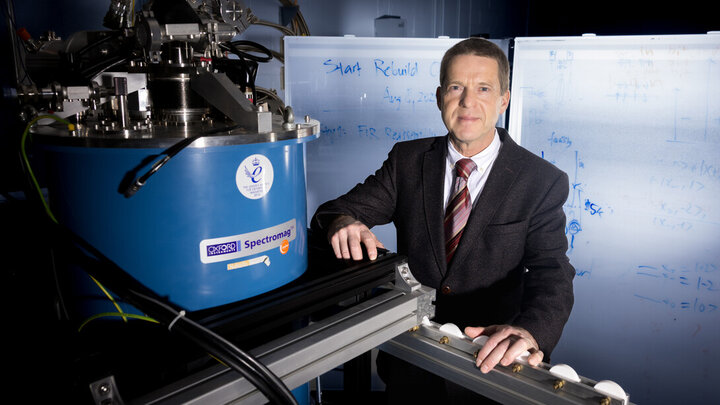

A UNK colleague, assistant physics professor Aleksander Wysocki, is also part of the EQUATE program. His research focuses on computational materials science, primarily magnetic materials and their applications in spintronics, sustainable energy and quantum information technologies.

In the following Q&A, Armstrong shares his perspective on quantum research, interdisciplinary collaboration and what makes EQUATE such a vital program for Nebraska and beyond.

Why is the EQUATE program so important?

EQUATE ultimately seeks to find applications of quantum phenomena, the so-called “second quantum revolution,” where quantum behavior is utilized to accomplish some useful task. Working in this field provides training in fields and techniques that should be relevant in the development of high-tech work, and workplace development is one of the key outcomes of the EQUATE grant. There is also an outreach component to the grant that runs programs around the state to generate interest in science.

What got you interested in this research area?

It’s kind of a long story. My Ph.D. is in theoretical nuclear physics, but when I finished my degree, I wanted to do a post-doc in Europe, so I was less picky about the area of research. It turned out that I got a post-doc at Lund University in Lund, Sweden, in a group that works in the theory of these cold atoms, so I tried to apply what I knew about nuclei to this new field.

Fast forward to summer 2019, when I got an email from Christian Binek, a UNL professor who would be the scientific director of EQUATE, about joining this grant application. I agreed, and a few months later we were told that our application was selected by Nebraska EPSCoR to go to NSF EPSCoR. At that time, I was between projects, and after talking with some of my research collaborators, decided to start this project involving impurities in dipolar BECs. It was close enough to what I had been doing before and would give me a chance to learn new techniques.

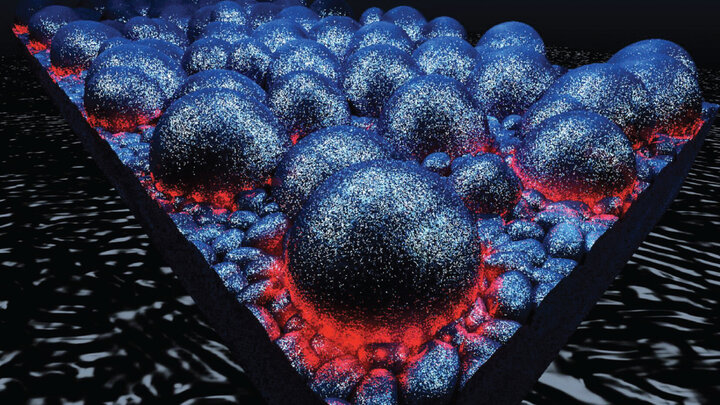

What are your biggest discoveries?

For EQUATE, we saw that if you disturb this dipolar BEC by placing an impurity, the response of the BEC is anisotropic regardless of the shape of the impurity. This would be like if you are dropping a stone in a pond, the ripples are circular regardless of the shape of the stone. So, it turns out this holds for our dipolar BECs, as well, except the ripples would be ellipses instead of circles.

How do you measure success as a researcher?

There are the typical metrics like papers authored, grants awarded, students mentored, etc. And indeed, it would be hard to argue that someone who produces a lot of those things is not successful. However, in a more basic sense, I think if you are progressing in a line of inquiry and you are advancing along that line, then you are learning new things and advancing your understanding about something new, and that is some kind of success. If your work is cited by others, then not only are you learning something, but you are also helping to advance your field.

What’s the most enjoyable part of research?

Working with many different people. Science is international, and working with people from many different backgrounds has been very interesting and rewarding. It helps you get through a difficult spot in a project when you have such great people involved in the project with you.

How do you balance research and teaching? Do they benefit each other? In what way?

It can be tricky, especially if one does not like to multitask, because then you may feel that you are doing both tasks (research and teaching) poorly, rather than focusing on doing well in one of them. During the academic year, I make sure my classes are where they should be and then fill in the remaining time with research activities.

They do benefit each other. In physics, a lot of what we teach at the undergraduate level is physics that was researched 200 to 300 years ago. Indeed, even “modern physics” covers the physics of around 1900 to 1930, so students might not see the connection between what they are hearing about in class and what they hear about in science news or see on posters about what their professors do. But in doing research, we can describe that connection between what they are learning in their classes to what is going on in physics now, which can help motivate our students. This was important for me as an undergraduate, as I started as a chemistry major interested in atoms and molecules, and when I took physics for the first time, I thought all these springs and inclined planes were not really all that interesting. But through talking with my instructors, I could eventually see how it all fit together.

Teaching also can benefit research when communicating your results. You can often tell when watching a scientific presentation if the presenter teaches a lot or not, as they (often) can communicate their work in a clearer way or a way that’s more accessible to a non-expert audience.

One emphasis of the EQUATE program is outreach. Why is that important?

The outreach component of EQUATE is important because it first maintains Nebraska EPSCoR’s programs working with K-12 students as well as the Tribal Colleges in Nebraska. Keeping students’ interest in science is important to keep the pipeline of future scientists open and more generally keeps the public a little more aware of what we are doing. Given the challenges in funding science may face, engaging the public has become very important.

On the outreach side, I have participated in many of the activities the physics department does at UNK, such as Science Day and “Astro Friday” planetarium shows, and I worked with my fellow UNK EQUATE collaborator Alex Wysocki in a session for our department’s 2024 summer camp.